By Jordan Marie Whetstone

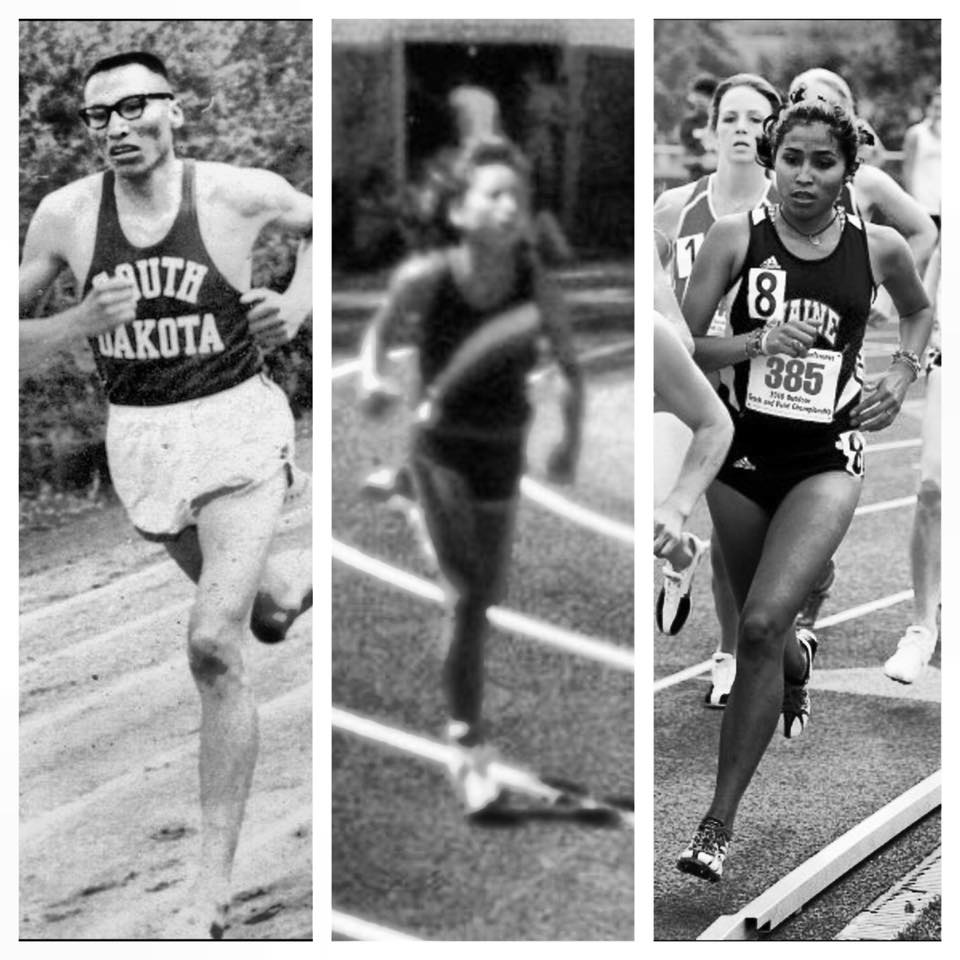

Founder/Executive Director of Rising Hearts

I’m a fourth-generation runner. Born in South Dakota, a member of the Lower Brule Indian Reservation—a community I was part of until we moved to Maine when I was 9 years old. Running is in my family, as it is for many Indigenous families where running has strong and long routes. It’s part of our culture. I felt part of something, when it came to my family. I was in the cool kids’ club of family runners. I ran because my superhero, my lala (grandfather), did and was extremely well known for his success and passion for running and wellness. I ran throughout school, often being the only kid of color, where it was obvious I was different. But when it came to running, I felt like I was accepted and where I felt like I belonged.

Outside of running, it was a struggle to fit in. I was ashamed of being the brown-skinned girl in a very White town, a town where I experienced racism and prejudice for the first time. It also showed me that those attitudes existed every time I went back home to South Dakota. I didn’t want to stand out, didn’t want to be different. Through ups and downs and facing an eating disorder that began in high school and I had to confront in college, I fell in love with running. Right around the same time I was reclaiming my Indigenous identity as a Lakota woman, a Native professor suggested I attend a round dance at Penobscot Indian Nation—that it all changed. A teammate of mine joined me and as soon as we walked through those doors into the gymnasium, a familiarity was there instantly. Those auntie and grandma laughs we all have, I heard it. I heard the drums, the heartbeat of our Nations. I felt like I was at home, even though it wasn’t a community I came from. Everything changed.

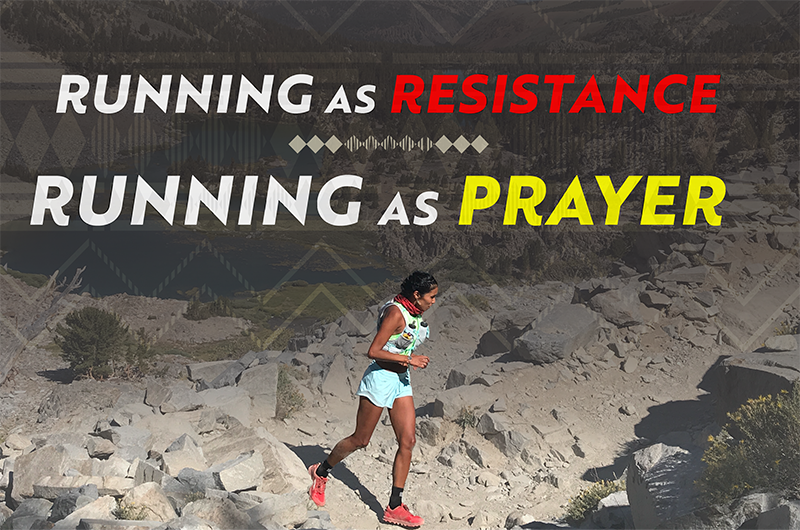

The Sacredness of Movement

Running and reclaiming who I am began to intertwine. Both reminded me I was on the path I was meant to walk—or rather, run. The more I ran, the more grounded I felt. As I was healing from my eating disorder and being proud and more comfortable in my own skin, it was the trails I ran on endlessly that gave me my energy and will to keep running and keep going. It was a safe place for me. It was my place to lean into. The lands that embraced me and allowed me to be vulnerable. The more I reconnected to my Lakota identity, the more I felt the land welcoming me back. I had a conversation with my friend, Dr. Lydia Jennings, about blood memory, while we were running together and filming her own story. Blood memory, in the way that the lands remember you and how our bodies are connected with the lands. The memories of feeling like you’ve been there, or a certain emotion that comes with it. A connection that has been lost for so long because of Colonialism. A kinship I believe every single person can benefit from. That convergence gave me deep appreciation not just for who I am, but for the strength of Indigenous womanhood and the sacredness of movement.

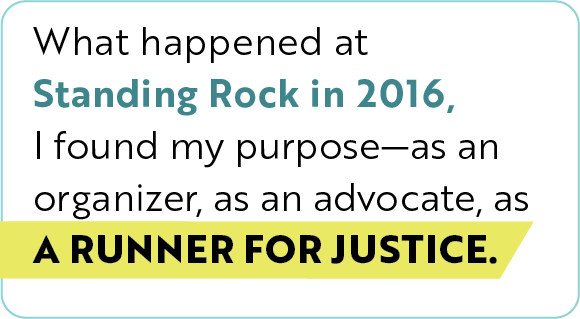

What happened at Standing Rock in 2016, I found my purpose—as an organizer, as an advocate, as a runner for justice. Since 8th grade, I wanted to move to Washington and be an advocate for Indigenous Peoples. That dream came true in 2013 after college. I worked for Native nonprofits, for a Maine congresswoman, until I landed at the Administration for Native Americans. Outside of work, I had been blogging, attending protests, supporting the voices of others, but I hadn’t yet taken the lead. That changed when I was asked to help organize an event to welcome the Standing Rock youth runners who were running over 2,000 miles from Cannonball, North Dakota to Washington, D.C. They were carrying the message: Mni Wiconi—Water is Life.

Gaining Encouragement and Purpose from Loved Ones

Over the course of two weeks, a friend and I pulled together permits, logistics, and volunteers. We ran from the Supreme Court to the Army Corps of Engineers, where we protested for hours. Days later, my grandfather passed away from cancer. He had always been my biggest supporter—especially in youth advocacy work. And two days after his passing, I turned on the news and saw those same Standing Rock youth being attacked by dogs.

Everything connected in that moment—grief, injustice, purpose. The fire lit in my heart that day has never gone out. I realized this is what I was meant to do: show up, organize, run, and fight for the people. It has led to hard times in my life, struggling to keep it all together. Dealing with anxiety and depression, the feeling of having to take it all on; something that resonated with other community voices. My running during this time was more in an ebb and flow state, getting in any miles I could between work, organizing meetings, panels, radio talks, and interviews. But when the anxiety and depression was heavier, I leaned into running more. Feeling that organizer burnout and struggling with defining what those boundaries were for myself. To be honest, several years later, I’m still struggling to set those boundaries, now with a 3 and a half year old and 20-month twin girls, too. Healing, finding ways to care for yourself, and movement, is never linear. It’s a day-to-day intention, setting and aligning myself with what my needs are.

My fire only grew when I learned about Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a young Native woman in North Dakota who was murdered in 2017, her baby taken from her womb. That horrific act broke something in me—but it also woke something up. It reminded me that the world often treats Indigenous women as disposable. That we are not seen. Not valued. And as a survivor of violence myself and not knowing a single Indigenous woman and woman in my life free of trauma and violence, it was clear that these aren’t isolated incidents.

Dedicating Miles to the Memories of Others

I had to do something. I started dedicating my races to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). During San Diego half marathons in 2018 and 2019, I pinned my bibs with MMIW written across them. A few people asked questions, and it sparked some small conversations. And I tried to learn as much as I could, share as much as I could and donate.

At the 2019 Boston Marathon, while being a chaperone for the Wings of America youth, I decided I would honor our stolen sisters and kin the best way I knew how—through running. Twenty-six miles. Twenty-six names. Twenty-six prayers. With each mile, I said their name and carried their memory forward, step by step. I said a prayer for their families. I said a prayer for our communities. And then I tried to enjoy the remaining parts of that mile before the next one began. It was one of the most spiritual and emotional experiences of my life.

After the race, the weight hit me—physically, mentally, emotionally. The grief, the violence, the injustice—none of it was abstract anymore. I am someone who feels they are more of an empath, feeling the emotions of others and often carrying them with me. Families started reaching out: “That’s my sister.” “That’s my mom.” “Can you run for my auntie?” I’ve committed every race since then to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples (MMIP). In 2019 alone, I ran for 106 Indigenous Peoples—106 miles for 106 prayers. I ran until my body gave out with Achilles tendonitis, which eventually became a tear. That’s when I learned: if I wanted to continue running for justice, I needed to also run for my healing. I needed to set boundaries. So, I took steps to be more intentional by taking time off, healing, recovering, and seeing my therapist again.

Running is sacred in our cultures. I come from four generations of runners. And for many, running is community. It’s a ceremony. It’s tradition. It’s becoming a woman. It’s carrying messages and prayers. It’s running prey to exhaustion. It’s how we connect to each other and to Unči Maka—Grandmother Earth.

Running for the Health of All Nations

When the pandemic hit in 2020, I launched the Running for the Health of All Nations virtual 5K. Our goal was to raise $5,000 for Native and Black communities hit hardest by COVID. We raised over $18,000, with 700 people joining in solidarity. It reminded me why I do this work—to show that movement can be more than personal. It can be community, action, learning something new, and creating change for the next generations. Since then, we have held over 40 virtual movement events, with over $450,000 raised that we’ve donated back into community nonprofits and other groups through my nonprofit, Rising Hearts, an Indigenous led organization that centers kinship building, storytelling, and advocacy through movement.

In 2020, as the Black Lives Matter movement surged after the killings of George Floyd, Tony McDade, and Breonna Taylor, I paused to uplift and support Black lives. I saw our struggles reflected to us. Colonization. Erasure. Systemic racism. Our traumas are connected, and so is our healing. I began dedicating miles to Black and Indigenous lives, working to build intersectionality in the running space—where all BIPOC voices are uplifted and centered.

Being a woman of color comes with its own risks. Ahmaud Arbery should have been able to run freely. But he was hunted. Running as a woman, as a Native woman, means running with awareness that I, too, am a target. But I keep going. Because my freedom, my breath, my prayer cannot be taken from me. Not without a fight.

Running for the Health of All Nations

Now, as a mother, my relationship with running has evolved again. I’ve run stroller miles with my son and twins. I watch them change the moment we step outside—calm, curious, connected. In my postpartum journey, I ran the Kodiak Half Marathon in Big Bear Lake, California. I wasn’t at peak fitness, but I was free. I was full of joy. I ran for Kaysera. I ran among the pines, down singletrack trails, feeling held by the land and the creation stories of the people who’ve called those mountains home for generations.

Running has taught me balance, too. I’m learning how to show up for my community without burning out, which to me, is a constant work in progress. To set boundaries. To prioritize rest. Because this is lifelong heart work.

Running is my offering. It is how I carry forward the memory of our stolen sisters, the wisdom of my grandfather, and the hopes of the next generation. It’s how I stay connected to the land, to my people, and to myself. Until I no longer have to run for them, I will keep running—with purpose, with prayer, and with love.

Jordan Marie Whetstone is the founder and executive director of Rising Hearts, an Indigenous-led organization dedicated to amplifying community voices through kinship, movement advocacy, and storytelling. A filmmaker, she is codirector and producer for Know To Run and for the Patagonia film Run To Be Visible. Recognized in 2018 by the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development as one of the 40 Native Americans Under 40 awardees, Jordan is committed to running for justice and elevating voices to help transform the way we tell stories.